Just as there is a calm before the storm, a trough before a wave, so

too is there a lull after the storm is over, a serenity of sorts after the

last receding rumble of the major battle has gone, leaving only the

recurring echoes.

Such is the situation for the Australian forces, in the first days of

May 1918, in France. For, oh, what a battle the Kaiserschlacht had

been, and how well the Australians had done! But it had come at a

huge cost: 12,000 casualties. For the moment the Australians must

lick their wounds, rebuild their forces, and wait while Berlin works

out what to do next. Given that the Germans retain a large reserve of

troops, there is every chance that they will launch once more and the

only questions are when, and where? As ever, the most likely answers

are ‘soon’, and ‘at Amiens or Paris’.

Across the Australian Corps it is really only General Sir John

Monash’s 3rd Division who, restless for more action, continue to

push their line forward.

‘The Third Division had had enough of stationary warfare, and the

troops were athirst for adventure,’ Monash would later recount. ‘They

were tired of raids, which mean a mere incursion into enemy territory,

and a subsequent withdrawal, after doing as much damage as possible.

Accordingly I resolved to embark on a series of minor battles, designed

not merely to capture prisoners and machine guns, but also to hold

onto the ground gained.’4

Typically of Monash-organised excursions, they go well, with four

small battles between 30 April and 7 May yielding several hundred

prisoners who ‘impart a mass of valuable information’,5 numerous

machine guns, and a net mile of gained territory!

‘During the last three days,’ Field Marshal Haig admiringly records

in his diary after the last successful raid, ‘[the Australian 3rd Division]

advanced their front about a mile . . . The ground gained was twice as

much as they had taken at Messines last June, and they had done it

with very small losses; some 15 killed and 80 wounded; and they had

taken nearly 300 prisoners.’6

There is only one problem. The further Monash’s men push the

Germans back to the east, in their positions just north of the Somme,

the more it exposes their right flank to the Germans on the south.

‘I was in possession of much the higher ground,’ Monash would

recount, ‘and was able to look down, almost as upon a map, onto the

enemy in the Hamel basin, yet I was beginning to feel very seriously the

inconvenience of having, square on my flank, such excellent concealed

artillery positions as . . . Hamel Woods.’7

The obvious solution – and Monash attempts to persuade the

Australian Corps Commander, General Sir William Birdwood, to do

it – is to have the Corps attack south of the Somme as well, and take

the village of Hamel and the basin it is positioned in. Alas, it is decided

that for the moment the Australian forces there need more time to

recover from their exertions of the previous six weeks.

At least, while the bulk of Diggers wait for the next move to be

made, they are in a fine part of the world to be so waiting, with none

appreciating it more than the gnarled veterans among them.

Training in Cairo they’d been in the blistering deserts. At Gallipoli

they had been in bloody trenches. For two years on the Western Front

they’d lived like moles in bloody, muddy trenches, stormed at with

shot and shell . . . and now? Now, it is springtime in France! After

their heroic efforts at Villers-Bretonneux and the subsequent German

retreat, things are relatively quiet, as the Australian task is merely to

hold the Western Front defending the key town of Amiens.

It places them in one of the most picturesque parts of France,

a dreamy patchwork of wheat and maize fields, sheep and cattle

paddocks, abandoned small villages with cobblestone streets . . . and

many cellars still stocked with wine.

Yes, life does offer better things, but not for an Australian soldier

it doesn’t. There is even a bit of shooting to be done, to keep them

interested, and therein lies a tale.

For after the Germans’ failed attempt to take Amiens, the most

forward elements of the German Army have come to a halt at the point

where their offensive force has been equalled by defensive resistance. It

means that rather than holding a well-thought-out, superbly engineered

major system of built-up trenches, the exhausted Germans have simply

dug in the best they can in the chalky soil, wherever they can, as they

work out their next move. They no longer hold their own line with a

combination of concrete pill-boxes, dugouts, rolls of barbed wire and

carefully positioned machine-gun posts that can deliver devastating

fire on any intruder within 400 yards. Instead they occupy a series of

non-continuous trenches, with dangerous gaps between, guarded by

rolls of barbed wire here and there, and machine-gun posts scattered

sporadically rather than bristling from every part.

And there is no effort to strengthen their line! This is, in part,

a measure of the Germans’ exhaustion and diminished resources, and

also because their commander, Erich Ludendorff, has forbidden such

consolidation on the reckoning they must keep the Allies guessing about

whether they intend to advance once more, stay, or retreat.

Hence, what the Australians are up to now – holding the ten miles

of the Western Front that they have just so wonderfully held over

the last six weeks, with three Divisions in the front-line trenches at

any time, and one Division in reserve for two weeks at a time before

rotating. Far and away the most important part of the line they are

holding is that which lies in front of the French town of Amiens,

stretching from the River Somme, to the Roman Road, a cobblestoned

thoroughfare – first built by the Romans nearly two millennia earlier

– which goes east from Villers-Bretonneux to Saint Quentin. From

atop the highest point of the Australian section – Hill 104, just 3000

yards back from the front-lines – you can see the full gloriousness of

the French countryside, the rich mosaic of ancient villages, even more

ancient farmlands boasting clover and wheat fields, and out to the

left the timeless Somme, in a marshy valley winding its majestic way

through the dreamy landscape. Ah, and of course, from here you can

look straight across to German-held territory, including a dangerous

bulge in their line around the village of Hamel and, just behind it, the

hill of Wolfsberg, nearly as high as Hill 104 and covered with German

observers watching them in turn.

They’ll keep.

For now, the tone is set by a few sentences in the diary of one

Australian soldier occupying his trenches in this early part of May.

‘I wonder if I’ll ever see Australia again,’ he writes. ‘This life seems

so unreal at times and one can see no end of the war in sight. The

wood in front of us looks so beautiful in the sunlight and life seems

so good, yet there is death in the . . . shells and whistling bullets.’8

Even though in comparison to what these men have lately known, it

is all quiet on the Western Front, in many ways it is a little too quiet.

So quiet, in fact, if you cock your ear to the wind right now, you

will hear something extraordinary.

For, yes, now, in the area a mile or so back from those front-line

trenches, what is this that the Diggers have dragged out of an abandoned

chateau, put on a ‘shell-torn cart’ and dragged back here to the Diggers’

dugout? Why, it is a grand piano! A huge one. A grand grand piano.

Well, yes, it had been found midst ‘sheets of music . . . strewn all

over the floor, pictures & costly ornaments broken by shell fire, lovely

cushioned chairs broken’, and has taken a bit of a hit, suffering ‘4 shrapnel

holes in the woodwork’.9 But while the chateau itself looked fine from

a distance and was ruined up close . . . this, this is quite the reverse!

For now look.

Up steps a Digger with intent, and with the grand theatricality of

the maestro he maybe once was, his fingers stretching skywards before

gliding downward, he starts to play.

And play, and play, and play! See his fingers flow over the keyboard

with impossible speed. Hear the music float out over the bloody trenches

that serve as ugly slashes through the fields of dandelions, daisies and

daffodils, and watch what happens now.

For as his chords float forth, and the battered piano delivers a

pitch-perfect performance, heads start to bob up in yonder trenches.

The bloke on latrine duty throws down his shovel, and walks on

over. Passing platoons stop their weapons check and gather round.

The bloke hauling the mess-cart stops, and comes on over. Diggers in

dugouts come on out, like moles from a hole after the winter is over,

and springtime has arrived. A crowd of mud-men gathers around the

messy maestro, as still he keeps on playing.

Is it Brahms? Beethoven? Liszt? Mozart? Chopin? One of them

German or Austrian coves, anyway?

Buggered if they know, most of them. But they know the Digger

can play and play extraordinarily well, as the birds sing, and bombs

burst in the distance.

A passing English major is so impressed, he asks will they sell the

piano.

No.

Can the Germans in their trenches over yonder hear it, too?

They hope so. For they, too, must surely say, Play on, young man,

play on. Das ist gute Musik!

Still the Digger does not look up, transported to a place far away,

just as they all are, magically transported to a place where men aren’t

set on killing each other, where you can see your families, and go out

on a Saturday night with your best girl, and the following day have

Sunday roast with Mum and Dad and Auntie Dot. Where you can go

to bed every night, with full confidence that you will see the sunrise.

Oh, play, Digger, play, as these Australians far from home soak up

every note, many of them luxuriating in the finest silk panties beneath

their muddy strides, their luscious drawers purloined from the drawers

of Madame who had left yonder chateau a few days before. One of

them stands there dressed for a joke as a combination of a fine French

gentleman and lady with ‘a tall black hat & white lace parasol’10 that

he has also ‘souvenired’, as the Australians are pleased to call looting.

‘Lor’ isn’t it funny,’ one Digger notes admiringly in his diary of his

brothers-in-arms. ‘They take nothing, not even war, seriously, though

in the trenches Fritz learns what they are made of.’11

And yet while it is one thing to be such brothers-in-arms and feel that

deep bond that comes with fighting for your life and the man beside

you, while he does the same for you . . . it is quite another when your

brothers-in-arms are your actual brothers, flesh of your flesh, blood

of your blood, spirit of your spirit.

|

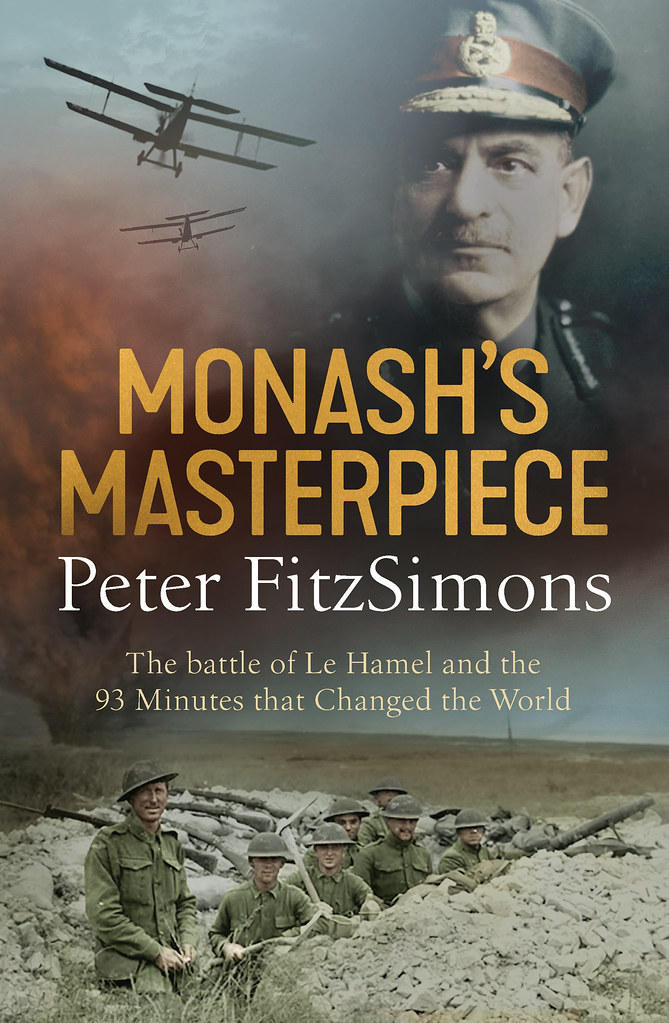

| Men of the 15th Battalion, on the day of the fight at Hamel, worn out and asleep under camouflage which was found covering a German trench mortar in Pear Trench. (AWM E02664) |

The Geddes brothers of the 13th Battalion are a case in point,

and the middle one, Cliff, is right here, right now, soaking up the

music. Originally from Warialda, up Moree way, the brothers Geddes

– 35-year-old Sergeant Aubrey Geddes, 30-year-old Corporal Cliff

Geddes and 24-year-old Sapper Stanley Geddes – had all been bank

clerks before enlisting, and have been in the thick of the heavy fighting

ever since. Aubrey, known as ‘Boo’ to the family, is with B Company

of the 13th Battalion, while Cliff is with D Company of the same, and

Stanley is with Brigadier Pompey Elliott’s 15th Brigade, serving with

the 15th Company Field Engineers.

Like his brothers, Cliff – a distinguished looking fellow, who is neat,

as Diggers go, and careful with his presentation, just as he had been

raised – is dead keen to finish this damn war, and get home as soon as

possible. Like them all, he is proud of Australia’s accomplishments in

these parts, but a little pissed off that so often the Australians seem to be

on their Pat Malone when the heavy lifting is to be done against Fritz.

‘It was a great performance of our Australian lads to drive Fritz out

of this town of Villers Bretonneux,’ Cliff writes in his diary this evening.

‘Lately it seems always a case of the Pommies losing a position, & our

chaps holding Fritz, or having to win back what the Pommies lost.’12

And it is dangerous, make no mistake. A bloke could be killed at any

moment. Oddly, Cliff worries more about his brothers – particularly

Boo even though he is in the same Battalion – than himself, but that is

just the way it is.

‘Haven’t seen Boo since Monday night, trust he’s OK, they are not

getting the shells in the front line we are back here, & if there’s no hop

over, I think he’s pretty right, though one never knows what minute

he’ll be hit at this game.’13

The two key questions that a lot of the Diggers want answered right

now are: firstly, what will the Germans do next?; and secondly, when

will the bloody Yanks dip their bloody oars in?

You see, it seems clear that the Germans are girding their iron loins

for their next attack, which will be a big one, there can be no doubt.

Since Russia pulled out of the war after the Bolsheviks took over late

the previous year, German forces previously on the Eastern Front have

been flooding into France at the rate of 20,000 a week, and as the

Kaiserschlacht showed, Germany is eager to win the war, before the

weight of the Americans, who, in turn, are now flooding into France

at the rate of 60,000 a week, can be felt.

But while the Germans arriving are fighting, the bloody Yanks aren’t

and it is a real problem for those, like the Australians, who are holding

the line.

Typical is the view of the British officer, Captain Hubert Essame of the

8th Division, who had recently fought by the side of the Australians as

they re-took Villers-Bretonneux. His experience has convinced him that

the Australian troops are the best in the war. But great boon that they

are to the exhausted British forces, they will not be remotely enough.

‘A year had now passed since the Americans had entered the war,’

Essame would note, ‘and yet, apart from four good divisions in quiet

sectors on the French front, they had contributed virtually nothing to

the death struggle . . .’

Credit: Reprinted from Monash’s Masterpiece: The Battle of Le Hamel and the 93 Minutes that Changed the World by Peter FitzSimons. Hachette Australia, RRP: $35.00. ISDN: 9780733640087.